https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-022-04133-1

EU climate plan sacrifices carbon storage and biodiversity for bioenergy

Third, Europe could restore habitats. Approximately 30–70% of assessed populations of most major European taxa have a conservation status of ‘poor’ or worse (see Table S2). Biodiversity priorities include buffering the remnant habitats on which rare species survive, and preserving the 20 Mha to 30 Mha of diverse, semi-natural grasslands.

Europe could reasonably choose a mix of these goals for its land future, but they all require a smaller footprint.

Bioenergy and land

Although the European Commission says otherwise, its Fit for 55 plan sacrifices carbon storage and biodiversity for extensive bioenergy. Its own modelling predicts that yearly use of bioenergy will more than double between 2015 and 2050, from 152 million to 336 million tonnes of oil equivalent. That requires a quantity of biomass each year that is twice Europe’s present annual wood harvest, and eight times the portion of that harvest used for bioenergy today.

Modelling by the commission also projects large effects on forests and land use: by 2050, Europe will devote 22 Mha of cropland to energy crops, or roughly 20% of cropland, and import four times as much wood for bioenergy. It will also lose 17 Mha of cropland for food and feed. Roughly half of Europe’s semi-natural grasslands will disappear to generate energy crops or host intensively managed forests. The commission probably underestimates these effects on land and forest felling by stating that bioenergy will use 2.5 times the maximum available forest residues estimated by other sources. Overall, the plan means less habitat and carbon storage in Europe, and continued or greater outsourcing of Europe’s footprint.

A proposed EU anti-deforestation law will not halt these effects. This law will prohibit imports of some commodities (such as soya beans and beef) produced on newly deforested land. But as long as Europe’s use of existing agricultural land in other countries is maintained or grows, global agricultural lands must expand unless other countries reduce their footprints by even more to compensate.

Nor can a proposed nature-restoration law shore up Europe’s biodiversity without even more outsourcing, if expansion of bioenergy leaves no land to restore as native habitats. Other bioenergy effects are also harmful. Although energy crops provide more habitat for common species than do annual crops, the loss of semi-natural grasslands means less habitat for many rare plants, butterflies and birds. Removal of almost all wood-harvest residues from forests contradicts the priority to leave more dead wood for many rare species.

Carbon accounting error

Driving the push for bioenergy is the belief that it will reduce greenhouse-gas emissions by replacing fossil fuels. But the EU’s carbon accounting ignores the consequences of increased land use because the energy laws treat bioenergy as ‘carbon neutral’. Although greenhouse gases from the fossil fuels used to produce biofuels count as emissions, carbon stored in the biomass and emitted by burning or refining it does not.

Crucially, this assumption ignores the opportunity costs of agricultural land and wood. The typical justification is that the carbon emitted by burning biomass is offset by the carbon absorbed by growing the plants. But land is required to grow plants. Using cropland for energy crops means this land cannot produce food, which helps the climate by reducing the need to convert other lands. More wood for bioenergy means less carbon in forests. Land is not ‘free’.

Fit for 55 proposes some restrictions on biomass production. It caps biofuels from food and feed crops at near 2020 levels and excludes them from shipping and aviation fuel targets. Biomass loses its carbon-neutral status if it is produced on land gained from newly cleared forests or is harvested from some primary forests. But energy crops grown on existing agricultural land and wood harvested from most of the world’s forests still count as carbon neutral.

The commission says that strengthened climate rules on land use compensate for this problem. These rules require that countries modestly expand their forest carbon sinks and correct some accounting abuses. If bioenergy growth leads to more wood harvest in Europe, the commission argues correctly, the emissions should be reported somewhere in Europe’s land-sector balance sheet.

But distorted incentives persist for the simple reason that biomass remains carbon neutral to energy users. Factories, power plants, airlines and ships will receive climate credit for replacing fossil fuels with biomass regardless of the real effect on carbon storage, either in Europe or abroad. If a Danish power plant imports and burns Romanian wood, the rules could require Romania to make more mitigation efforts to compensate for the reduced carbon storage. Regardless, the Danish power plant still has incentives to do so, despite increasing carbon in the atmosphere. And if new land-use rules lead Romania and other EU countries to restrict wood harvesting to preserve their carbon stocks, the bioenergy rules will drive even more outsourcing.

Although bioenergy can reduce net emissions over long time frames, the consequence either of harvesting more wood or diverting cropland to bioenergy is likely to be increased carbon in the air for decades. The commission’s published Forest Strategy, in a single sentence buried in the middle of a long document, agrees with the overwhelming literature that harvesting stem wood for bioenergy increases atmospheric carbon for decades, even when factoring in reduced fossil-fuel use9. Diverting a hectare of European cropland to energy crops is also likely to increase carbon in the air for decades when compared with either saving one hectare of forest or savanna abroad, or even reforesting a hectare in Europe10.

Lessons and solutions

A climate planning process such as the Fit for 55 strategy highlights the error of treating biomass as carbon neutral and therefore land as free. The plan allocates resources, including land, among competing uses to reduce emissions. Ignoring land’s alternative ‘carbon value’ when diverting land to bioenergy guarantees its inefficient use.

The simplest solution is for the EU to stop treating biomass from energy crops and wood harvests as carbon neutral. The European Parliament adopted an amendment to freeze the quantity of woody biomass that counts as ‘low carbon’ at each EU country’s 2020 level of use. If this rule survives negotiations with the Council of the EU, it could limit the damage.

Unfortunately, the parliament failed to bring all energy crops under the same cap applied to biofuels derived from food and feed crops, despite their similar effects on food production and cropland. Unless the EU fixes this problem, the more it restricts fossil carbon, the more it will encourage diversion of cropland to energy crops and outsource its food production.

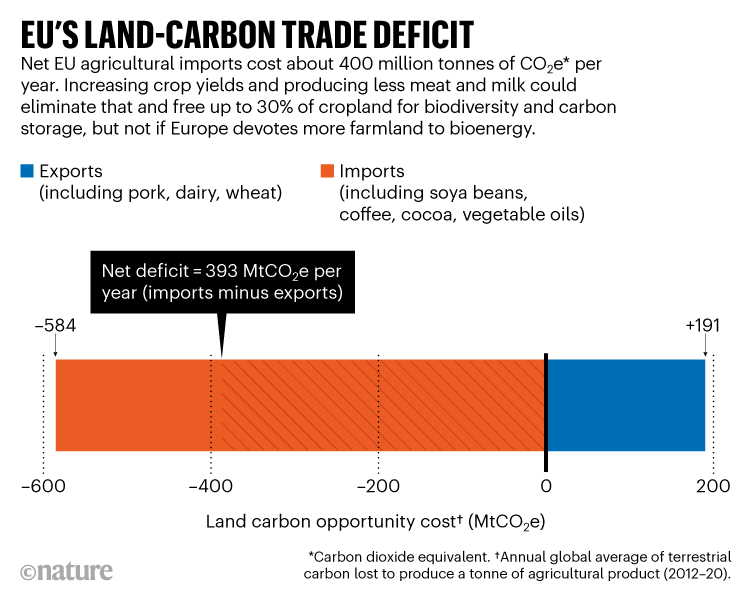

The best solution is to incorporate the ‘carbon opportunity cost’ of land use into the accounting of emissions from bioenergy in all climate and energy laws. This cost can be measured simply as the carbon that could otherwise be stored by regrowing native vegetation. A superior approach would use carbon opportunity costs, as we have done here, to calculate the average carbon cost to reproduce the same food elsewhere. This approach does not require a switch to consumption-based accounting but recognizes that land use has an opportunity cost, which should be factored into the life-cycle analyses of bioenergy used by the EU.

Saving terrestrial carbon and biodiversity starts by reducing, not outsourcing, Europe’s land carbon footprint. Adapting Europe’s plan can deliver a more beneficial land future.

Nature 612, 27-30 (2022)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-022-04133-1

No comments:

Post a Comment