https://www.wakeuptopolitics.com/p/a-readers-guide-to-the-big-beautiful-26e

A Reader’s Guide to the Big Beautiful Bill: Part 2

Wi-Fi, Mars, air traffic control, and more.

Hey, everyone! I’m back with Part 2 of my multi-part series walking you through how to read the One Big Beautiful Bill Act.

Today, we’ll break down Title III, the Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs Committee section, and Title IV, the Commerce, Science, and Transportation Committee section.

Here’s Part 1 if you missed it. For this installment, I’ve made PDFs for both titles (linked below), to make it even easier to read along with the specific segment that we’re covering.

As you read through today’s newsletter, I encourage you to try and pick out at least one thing you like about the bill (even if you’re a Democrat) and at least one thing you dislike (even if you’re a Republican). Also, try to think about one thing you learned that you didn’t know was in the bill — and one thing you still want to learn more about.

Feel free to drop your answers to any of these questions in the comments! And, as always, please comment with any new questions the newsletter raised for you, so I can try to answer those in a future edition.

With that, we’ll jump right in.

Title III: Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs (p. 55)

Here’s a link to the text of this title so you can follow along. It’s only one page! Shouldn’t be too hard.

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) is an agency set up by the Dodd-Frank Act in 2010 to regulate banks, credit card companies, mortgage lenders, and other financial services providers with an eye towards protecting consumers.

Here’s how this section would change the CFPB:

Not very helpful, right? We know a “12” is being changed to a “6.5,” but 6.5 what? Dollars? Employees? Apples?

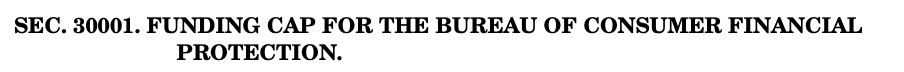

Well, some context is helpful: when Democrats started the CFPB, they set it up with a unique structure where its funding came from the Federal Reserve, instead of the annual congressional appropriations process like most agencies, so that it’s funding wouldn’t be thrown into question every year. If you look at 12 U.S.C. 5497 (below), which this section amends, you’ll see that “12” sets the CFPB’s maximum budget, which can’t be larger than 12% of the Fed’s 2009 operating expenses:

So, going forward, the CFPB’s budget cap will be nearly halved, to 6.5% of the Fed’s expenses, significantly disarming the agency.

We already saw a similar provision in Part I. Language like this means that a previous act of Congress appropriated a certain amount of money towards a certain goal; under this provision (a “rescission”), any funds in that pot of money that haven’t yet been spent are no longer allowed to be spent.

In this case, Public Law 117-169 is the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022; section 30002(a) consisted of $1 billion to fund projects improving the energy efficiency and climate resilience of affordable housing properties.

The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) regulates the trading of stocks, bonds, and other securities in American markets. Another creation of the Dodd-Frank Act was something called the SEC Reserve Fund; under the law, the agency is allowed to deposit up to $50 million into the fund each year (from fees it collects) and use the money towards anything it “determines is necessary to carry out [its] functions.”

Republican have long tried to kill the Reserve Fund, saying that it allows the SEC to get around Congress by unilaterally spending funds in ways not approved through the appropriations process.

15 U.S.C. 78d(i) is where the fund is established, so striking that subsection ends the fund once and for all. This section also says that any remaining money in the Reserve Fund will be redirected to the SEC’s Investor Protection Fund, which rewards whistleblowers who report financial fraud.

The Defense Production Act (DPA) is a 1950 law that gives the president the power to order companies to enter into certain contracts or expand production of certain materials if he deems it necessary to “promote the national defense.”

This section would add $1 billion to the pot of money that exists to help carry out DPA orders. President Trump most recently invoked the DPA in March with an executive order to boost domestic production of critical minerals, including by providing loans and capital assistance. (His Energy Secretary also designated coal as a “critical mineral” in May.)

Title IV: Commerce, Science, and Transportation (p. 56-66)

Here’s your link to this title!

This section appropriates $24.6 billion towards the Coast Guard, the single largest infusion of cash the maritime security service has received in its history. (For context, the Coast Guard’s entire Fiscal Year 2024 budget was $13.1 billion.)

According to the Coast Guard, the new funding will allow the service to procure 38 new vessels, 40 helicopters, and six aircraft, while also strengthening its ability to “counter drug and human trafficking, conduct search and rescue, enhance navigational safety and enable maritime trade.”

Remember how I told you in Part I that this bill was an interesting tour through things you might not have known the government was involved in? Well, here’s a great example of that.

Let’s start with a physics lesson! In order for any wireless device — like a phone, radio, or TV — to send or receive signals, it needs to have access to a specific frequency on something called the electromagnetic spectrum. But spectrum is a finite resource; if too many devices are trying to use the same frequency, their signals can interfere with each other and stop working.

Here’s where the feds come in. In the U.S., slices of the electromagnetic spectrum are auctioned off by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), so companies like AT&T and Verizon compete to buy the right to transmit signals on specific frequencies. This brings order to the airwaves, and generates some nice revenue for the government.

But the FCC’s authority to hold such auctions lapsed in March 2023, and Congress never passed a law extending it, so there hasn’t been an auction since then. This section would strike the old expiration date and give the FCC back its auction authority until September 2034:

In total, the section calls for 800 megahertz of spectrum to be auctioned off. Like I said, spectrum is finite — so it’s not as if new spectrum has suddenly been discovered. Instead, when an auction is held, spectrum is really just being allocated from one recipient to another.

In this case, the OBBBA calls for 500 megahertz of federal spectrum to be auctioned (that’s spectrum that’s currently used exclusively by the federal government, especially the Defense Department) and 300 megahertz of non-federal spectrum (which is likely to come largely from a slice currently reserved for unlicensed Wi-Fi use). That’s led to warnings from some corners that the OBBBA could lead to slower Wi-Fi, since newer phones and computers currently use this band of the spectrum to deploy the speedy Wi-Fi 6E, which they won’t be able to do once it’s auctioned off for use by mobile carriers.

I don’t know if you’ve heard, but we’ve had some high-profile aviation screwups lately.

The OBBBA tries to address that by appropriating $12.5 billion to the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), which will be used to do things like improve the agency’s telecommunications infrastructure, runway safety technologies, weather observation systems, and air traffic controller recruitment.

Currently, when private companies (think Elon Musk’s SpaceX or Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin) send rockets into space, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) establishes a no-fly zone over the launch area and devotes time and resources to ensuring that no airplanes are in the way. These services are provided to the companies for very little cost: the FAA only pockets a small fee the companies pay when applying for launch licenses.

Not anymore. Under the OBBBA, these companies will now have to pay a fee indexed to the weight of the rocket, which will go into a new fund to support the FAA office that oversees commercial spaceflight.

The fee will start out in 2026 as 25 cents-per-pound (up to $30,000), and then get higher each year until they reach $1.50-per-pound (up to $200,000) in 2033, and then increase along with inflation after that.

This would be somewhat similar to how airlines pay FAA fees to fly planes; that money then goes into a fund that supports air traffic control operations and airport improvements.

The author of this provision is Ted Cruz and — in case you’re wondering — the idea predates the Trump/Musk feud.

We’re going to Mars! Maybe. This section appropriates about $10 billion to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), including for the “Moon to Mars” program, a long-term initiative that hopes to once again land on the Moon and then eventually take humans to Mars.

Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards regulate how far vehicles have to be able to travel for every gallon of fuel, in order to improve energy efficiency and greenhouse gas emissions. They date back to the 1970s, though they’ve been increased over time.

Here’s what this section says:

When we venture over to 49 U.S.C. 32912, we see that the subsection in question outlines the penalty for violating the CAFE standards (which are themselves outlined in 49 U.S.C. 32902).

If we strike “$5” in this subsection and replace it with “$0.0,” the penalty for violating CAFE standards will now be calculated with the equation, “$0.0 ⋅ 0.1 miles per gallon that a car goes below the standard.”

Now, I’m no math expert. But my trusty calculator tells me that equation will bring the penalty down to — you guessed it — zero dollars, zero cents, no matter by how much a vehicle flouts the CAFE standards.

What’s going on here? Well, as we know, a reconciliation bill can’t make outright policy changes. It can only fiddle with spending or revenue. So, by that logic, Republicans can’t just do away with CAFE standards with the OBBBA. But they can set the penalty for violating CAFE standards to $0, effectively eliminating the standards by other means, since there will now be no penalty for violating the standards.

These are the sorts of games that the reconciliation process forces you to play; in this case, Democrats say the penalty removal will lead to fewer fuel-efficient vehicles, while Republicans argue that it will bring down the price of cars.

The two airports in Washington, D.C. — Reagan National and Dulles International — are the only commercial airports in the country that are owned by the federal government. However, in 1987, the government transferred management of the airports to the Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority (MWAA) in a lease agreement.

That lease was most recently renewed last year, in a new agreement set to last until 2100. Under that agreement, the MWAA pays the U.S. government about $7.5 million a year. But the OBBBA preempts that agreement, requiring the MWAA to pay the government $15 million per year starting in 2027 (with the amount subject to negotiation every 10 years to ensure that it never decreases in inflation-adjusted terms).

This is the governmental equivalent of searching for change under the couch cushions: finding any lever possible to raise a bit more revenue, in order to reduce the deficit impact of the OBBBA (although the revenue raised by sections is still trillions dollars short of offsetting the package’s costs). In this case, the change-under-the-cushion could make flying in and out of D.C. more expensive, if the MWAA pays for the near-doubling in its lease costs by raising costs for airlines, which the airlines could then pass on to consumers in added fees.

More rescissions from the IRA. This section would claw back unspent funds that were supposed to go to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), including for weather and climate forecasting.

The Travel Promotion Fund is the pool of money made available to Brand USA, a public-private partnership established in 2010 to promote the U.S. as a tourist destination. This section would reduce the annual amount that goes to this fund from $100 million to $20 million. (More change under the couch cushions!)

This section rescinds unspent IRA funds that were earmarked for subsidizing projects to produce low-emission aviation fuel.

And, finally: one more rescission, this one from the bipartisan CHIPS and Science Act of 2022. This section claws back funds that were supposed to go to the Public Wireless Supply Chain Innovation Fund, which works to support the deployment of 5G cellular networks by developing interoperable equipment that can be used by all companies.

That’s all for today! I hope you learned more about the OBBBA and how to read a piece of legislation. As always, leave your feedback in the comments so I can make future installments of this project as helpful as possible.

Thanks for following along.